How to create a believable world in video games?

The sense of immersion is one of the most important aspects of video games. This is what makes us forget about the real world while playing, and all the choices and consequences we make in a game feel as if they really happened.

The concept artist's job is to create such a world, among other things. Thanks to that, what is virtual becomes credible, and the adventure we experience becomes much more realistic. Emil Cegielski, Senior Concept Artist, recently awarded the prestigious Concept Art Award in the Video Game Environment category, talks about what a concept artist's work looks like.

Hi, Emil, you've been working at Techland for quite a long time, can we go back in time a bit and ask you how you got into gaming?

10 years ago, I joined the now defunct mobile games division - Shortbreak Studios, where I was a graphic designer and dealt with all graphic areas related to the production of mobile games. I learned everything about games there, because before that, I had worked as a graphic designer and animator in interactive agencies. I wasn’t involved in AAA game production until Dying Light 2 Stay Human, a project I've been a part of since the very beginning.

What would you say is the biggest difference between working in an agency and working in gaming?

I can actually point out one thing in common, which is that both here and there, the main task is to sometimes draw something nice. At the agency, the work of graphic designers must primarily look good and meet the client's requirements, while the work of a concept artist is much more complicated, because here, we design things that will appear in the game and they must be thought out primarily in terms of functionality. The final work of the concept artist, like my award-winning concept of a windmill, is the so-called executive concept. However, when working on a game, a black and white sketch that adequately reflects the atmosphere and fulfills the functions assumed by the game designers is often enough.

What is the ratio of such finished concept art to sketches in your work?

It depends on the stage of production. Currently, when making DLC, we start with the so-called. moods, i.e. highly aesthetic images through which we want to capture the atmosphere of a given story, but in the perspective of the entire production, it is about 20-15%. The rest of our designs don't have to be pretty, but they have to be legible. We can say we make blueprints or "technical drawings", i.e. visual guides to what will be introduced into the game.

By the sound of it, it's like working on storyboards, isn’t it?

Yes and no. Concept art is not a storyboard, but the logic of work is similar. Sometimes, we actually start with moodboards to show the atmosphere we want to create in the game, but more often, we get a brief with the demand for a given object. And the way it works then is we discuss the brief with the designer, I create sketches, after that we discuss them with contractors - artists and level designers, and we wonder if it fits the game as a whole. Next, we choose the final version of the object - a location, a prop, a character, etc., which gets finished by graphic designers, so that it can be put into the game.

At what point is the player most exposed to the work of concept artists?

Basically all the time - what the game environment looks like, e.g. the street, is a piece of conceptual work. What the player sees are not necessarily nice drawings, but functionalities that are easy for him or her to read. Imagine a button on the wall that the player has to press, so it must be a clear element of the game at first glance, and its properties, such as whether it is on or off, must be recognizable. In one of the quests in Dying Light 2 Stay Human, the player's task is to pull a cable and connect it to the appropriate box. Our job is to let the player know what element to grab, where to attach it and how to activate the mechanism. Similarly, the electric box - the one we create in the game - is not a 1:1 reflection of boxes we can see in real life, but a cursory glance should be enough for the player to know what kind of object he or she is dealing with.

The same principle applies to all aspects of the depicted world, for example, if we have a railway car, it must be clear that it is a subway car, a box in the street can be a telephone booth, a garbage can or an air conditioner outlet. We try to show this world in such a way that the player has no doubts that could spoil the reception of the game.

Earlier, you talked about functionality, which is the starting point for a given concept, could you give an example of that?

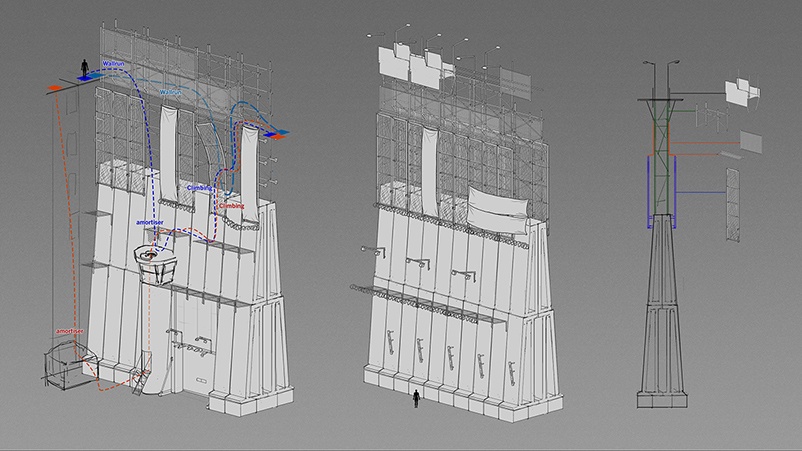

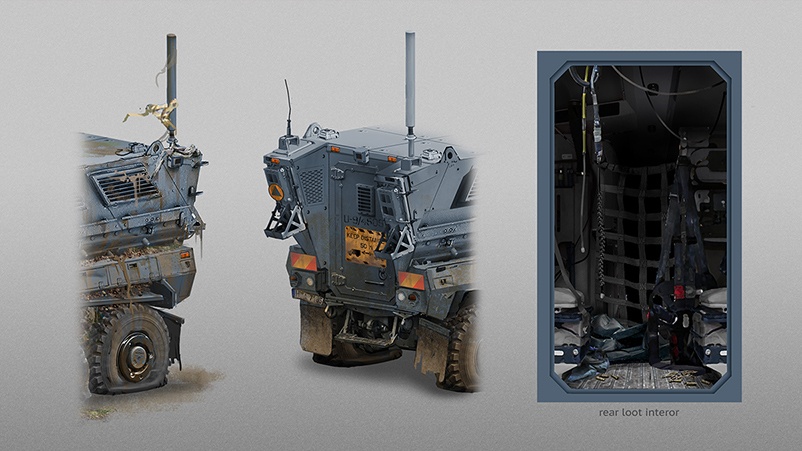

A good example of such an object is a military truck. This is an object that needs to be in a specific shape and immediately associate with trucks we see on the roads, and at the same time, enable parkour. The easiest way would be to bring a specific military truck into the game, but for obvious reasons, such as copyrights, we can't do it, so we design it based on the model we already have in such a way as to create points that the player will be able to grab while climbing, but at the same time, these handles cannot differ from what we associate with a real truck, because it will look artificial.

Parkour in general requires us to create believable methods of using it. Elements on buildings cannot look as if we added them so that the player can climb, but at the same time, they cannot always be elements of architecture, because there is a need for them to be movable, such as wiring. Let's take lanterns for example - on the one hand, they should look like city lanterns, on the other hand, in order for the player to be able to climb them, we have to design them so that their shape and surface meet the requirements of parkour. So we sometimes bend reality to our requirements, but we do it so that the player believes that this is how it can be in this world.

So you can say that, in a sense, you design the city, right?

Yes, but not only that. The world of a game is also the impressions that given places evoke in us. Level artists build the impression of e.g. claustrophobia or agoraphobia, or we want to take the player to a place that will be scary and together we figure out how to create an atmosphere that makes the player feel afraid and, at the same time, lets them know what needs to be done next. Guiding the player is a team effort.

In Dying Light 2 Stay Human, skills are also important in the perception of the city and the world we create in general. For example, when the player gains a new skill, they can jump further somewhere where the jump is very difficult and they manage to do it by grabbing a barely grasped element, which makes them really feel their progress, and we need to deliver such elements of the world.

Furthermore, with Villedor, we wanted to create a believable city, one where the player could walk around thinking "This could happen in my city". On the streets of Villedor, we will find, for example, a lot of advertisements on shop buildings, signs, elements of cultural life, e.g. graffiti, all of which reminds the player that this city once lived, it was like the city in which he or she lives and is now walking through the ashes of civilization. On the other hand, all these posters remind us of consumption and the negative features of our world of capitalism that has collapsed.

To sum up, all these elements build immersion at every level and thanks to them, the player can enter the world we have created, because our job is to create something that does not exist, but looks as if it did.

Can you tell us more about your award-winning piece of work?

Sure! It started with the need to build a windmill that would produce electricity in the post-apocalyptic world of Dying Light 2 Stay Human. At first glance, it seems simple, but let's remember that we are in a world where civilization has collapsed and this windmill cannot be built in the way we would with current technologies, because they are no longer available. In a way, I had to impersonate the builders of this world who create their structures from what they find and can reuse. Generally, a huge portion of a concept artist's work in a project like Dying Light 2 Stay Human is figuring out what people would do with very limited options.

What else, apart from the requirements of the depicted world, can constitute a limitation for a concept artist?

In Dying Light 2 Stay Human, I designed e.g. concepts of devices that are supposed to produce something, such as electricity, filter water, be an alcohol distillery or a bird trap. In our post-apocalyptic world, all this must fit on the roofs, where people live, and these have a limited area so, for example, containers for collecting water can take up a specific amount of space. When creating such objects, I have a few principles - it's supposed to look nice, fit on a specific surface, be understandable for the player and enable parkour - that amounts to quite a lot of limitations :)

Equally important, however, is the perspective of production costs, i.e. the valuation of how many hours it will take to produce a given object. Will the game engine pull it off, is the model not too physically complex, and is this level of complexity worth it? The windmill can be complicated, because it stops the player for a long time, but the water collector cannot be too elaborate, as the player does not focus on it for long.

That doesn't sound easy, do you have to do a lot of research?

Looking for references can be time-consuming, because you sometimes need to examine a purely technical element, e.g. mechanical hooks or how to attach a rope to a beam so that it does not break, and at other times, we look for something unusual, such as photos of a vending machine from the back, and then it turns out there are not too many photos like this on the internet.

Occasionally, there’s also a more complicated topic, such as creating a military camp in a city. First, I looked for various references and wondered why trucks, tents, or various crates stand in a certain arrangement and not otherwise. It turns out there are some rules on how to create such camps, so I had to read a bit on the subject.

Of course, I also watched a lot of videos about how to filter water on your own, how to make your own distillery, or how to build your own weapon.

So you're well prepared for the collapse of civilization, aren’t you?

Alas, I’m not, since I was looking for references mainly in visual terms :)

And does pop culture also provide concept artists with inspiration?

It does and we need to relate to it, because our players watch videos, play other games and compare them to our own.

As we’re about to finish, tell me what professional biases concept artists have, please.

Well, working on Dying Light makes me look at the reality around me in a completely different way. When I walk down the street or ride a bike and see something broken or destroyed, buildings covered with grass, some rags hanging down, I think "That would look cool in the game!" and I take pictures. So I collect images such as a rotten, flat surface covered with moss.

How does it feel to receive a Concept Art Award in the Video Game Environment category?

I was very surprised and really didn't expect it, because there are many concept artists in the industry who create excellent work, and the competition itself featured concept art from games released in 2022, including a number of more recognized titles than Dying Light 2 Stay Human, so I’m very happy indeed that my work has been appreciated.

Thank you for the interview and once more - congratulations!